Jonathan Dunsky

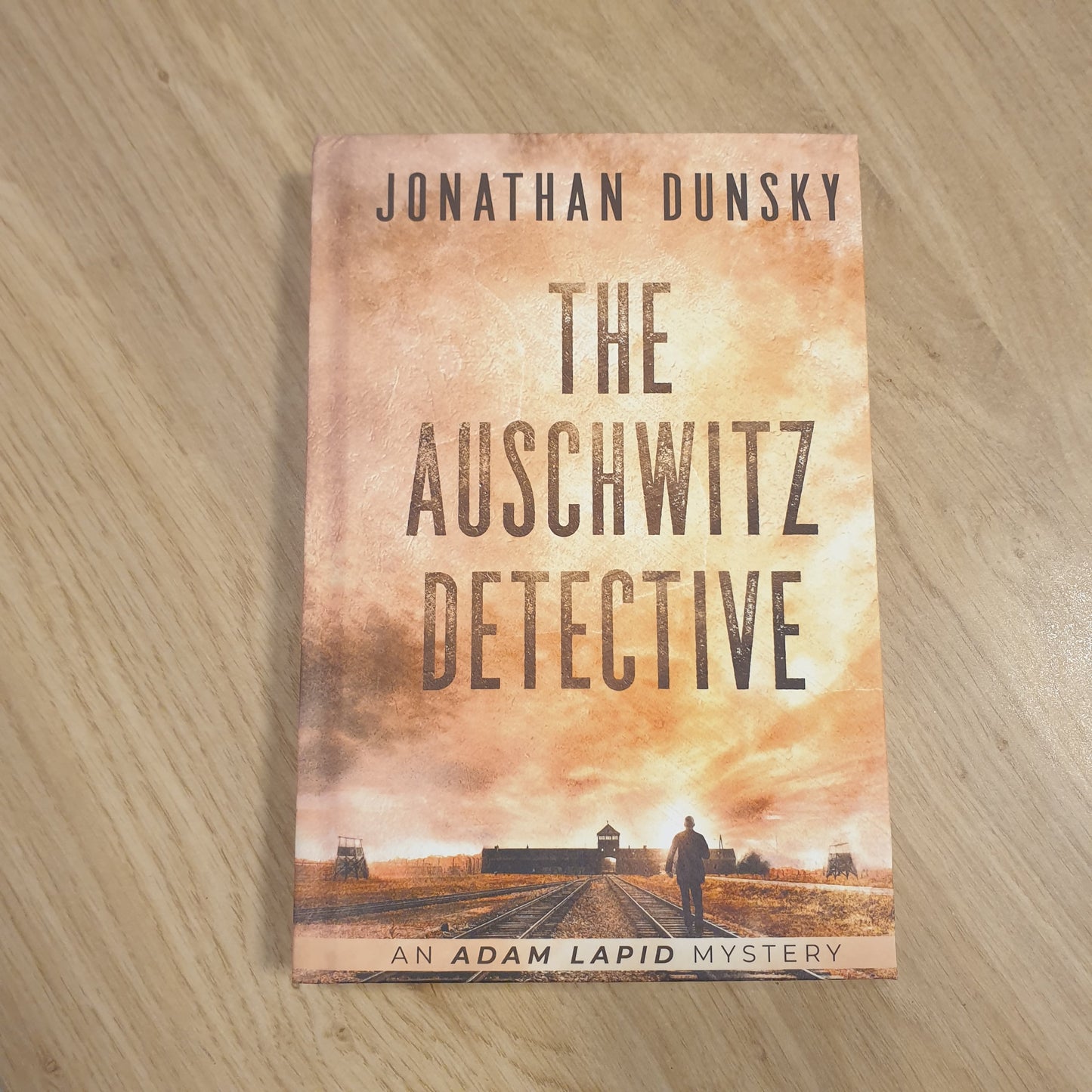

The Auschwitz Detective (Adam Lapid Mysteries #6) - Hardcover

The Auschwitz Detective (Adam Lapid Mysteries #6) - Hardcover

Couldn't load pickup availability

Book Description:

The boy was murdered in Auschwitz. The killer isn't a Nazi.

Poland, 1944: Adam Lapid used to be a police detective. Now he's a Jewish prisoner in Auschwitz.

Reduced to a slave after losing his family in the gas chambers, Adam struggles to find a reason to carry on living.

But when a boy is found murdered inside the camp, Adam is given the chance to be a detective again.

Ordered to discover the identity of the killer, Adam must employ all his wits to solve the mystery while surviving the perils of Auschwitz.

And he'd better catch the killer soon because the punishment for failure is death.

The Auschwitz Detective is book #6 in the Adam Lapid series. But since it's a prequel, it can be read first.

What Readers Say:

★★★★★ "A beautiful, heartbreaking story of the horrors of the holocaust."

★★★★★ "Incredible book, which left me speechless."

★★★★★"I literally could not put this down. I’m sorry I didn’t discover the author sooner. So many twists, and I simply fell in love with the main character, Adam."

★★★★★ "I have read many holocaust books but this suspenseful murder mystery in the unlikeliest of places is very different and so compelling. "

★★★★★ "I have read hundreds of books on the Holocaust and although I was aware of most of the things written I had not read a book as eloquently written as this one."

Here's a review of The Auschwitz Detective by CriminOlly, a YouTube book reviewer:

This is the hardcover version.

| Hardcover |

304 pages |

| Dimensions |

6x9 inches (15.24 x 22.86 cm) |

| Publication Date | March 28, 2021 |

| ISBN | 978-965-7795-12-5 |

| Publisher | Lion Cub Publishing |

Chapter 1 Look Inside

Chapter 1 Look Inside

CHAPTER 1:

I had never seen a man cry like that.

He lay prone on his bunk, second level of three, and bawled as though he had been driven mad. As he howled his pain out, his entire body quaked in jerky spasms, like an exposed heart beating erratically. His limbs jolted and flailed about, banging hard against the rough wooden slats that bore his weight.

Each sob was so deep it must have originated in the center of the Earth. It then chewed its way upward through rock and dirt, pierced the crust of the hard Polish ground on which the camp sprawled, burrowed through the floor of our block, and wormed its way into the crying man’s soul. From there it finally erupted from his mouth in a scream of such primal agony that it would have shattered our hearts at any other time, in any other place. Right then, it only hurt our ears.

The man had arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau eleven hours ago. Soon after that, his wife and six children were led to the gas chambers and exterminated. Someone had informed him of this fact five hours ago. His denial had lasted for three. He had been crying for the past two.

Other prisoners were giving him as much space as our overcrowded block allowed. Not out of kindness, but because his wailing was so unpleasant. No one comforted him, not even me. And I sat very close to his bunk, looking at him and wishing he’d shut up already and feeling ashamed for thinking that.

Not that I could have lessened his pain. No words held such power. His wife and children were dead. You couldn’t console a man in such circumstances. You had to let him cry.

He wasn’t the first man to cry in our block, as Auschwitz prisoner barracks were called, nor would he be the last. I had cried my first night here myself, knowing with an uncanny certainty that my wife and two daughters were dead. But no one had cried like this man. Even those who were loud, and many were, did not scream with such abandon, nor did their muscles clench and release as though they had come into contact with a live wire. Nor did their mouth gape wide in tortured silence before a delayed shriek burst through like fire from a flamethrower.

He cried like a man possessed by demons, like a man dispossessed by devils. I wasn’t sure about the former, but the latter was definitely true. For all had been taken from him, as it had been taken from each and every man who now had to hear him scream. And those who had taken everything from us were the closest things to the devil any of us would encounter on this side of death.

The man was in his late thirties, of average height, and had the fullness of flesh of a new prisoner. This would not last, of course. In the coming days and weeks, his muscles would dwindle, his fat would melt, his skin would shrink around his skeleton. He would look like the rest of us—gaunt and hollow-cheeked, with huge eyes and sharp bones and a sickly complexion. He would not look like a man any longer; at least not like any man he’d seen before the war, before he’d arrived here in Auschwitz.

In a way, he did not look like a man even now. Not with the endless tears leaking from his eyes. Not with the thick snot running from his nostrils. Not with the bubbles of spittle dotting his lips and the film of sweat on his forehead and shaven scalp. I wasn’t sure what he looked like. I wasn’t sure what I looked like. I wasn’t sure what I was anymore.

Apart from a number.

The number tattooed on my left forearm in bluish ink. That number was me, and I was that number. Sometimes it felt that this was all I ever was. That everything I had once been—father, son, husband, policeman—had been expunged, erased, eradicated so thoroughly that even the memory of those things was suspect, as though my life prior to arriving in the camp had been an illusion or a fevered dream.

I knew nothing of the crying man’s past. I did not know how he had made his living. I did not know his exact age. I did not know his hobbies or passions. I did not know his political or religious beliefs. I did not even know his last name. What I did know was that he was a Hungarian Jew, like myself. I knew that his first name was Gyuri. And I knew that he had married a woman, had fathered children, and, judging by the ferocity of his wailing, loved them dearly.

He and I had never exchanged a word. What I knew of him I’d learned from other prisoners—those who had greeted him upon his arrival in our block; those who had shared with him the grim new reality of his life.

And once it had sunk in, he had begun crying and hadn’t stopped since.

Another howl, this one achingly high-pitched, exploded from his mouth. It echoed around the dim interior of the block, making my ears ring. A number of the other prisoners groaned. Someone swore. A few cast baleful looks at the crying man. As usual, everyone was hungry and tired. We all craved sleep. But if Gyuri kept crying like that, sleep would be impossible. Even exhausted men cannot sleep in such noise.

There was tension in the air: a sense of impending trouble, like a honed blade poised for deadly use. That was why I was sitting so close to Gyuri, in spite of my throbbing eardrums.

There was a heavy thud from my left. A man had jumped down from his bunk partway up the block and was stomping his way over, his wooden clogs tapping an angry rhythm on the packed-earth floor. He was tall and angular, with a face as hard as a brick. There was murder in his eyes. I noticed his hands were balled into fists.

I knew who he was: a gruff, truculent Dutch Jew by the name of Hendrik. He’d been in Auschwitz for over a year. That alone said he was tough. But I had also seen him use his fists on more than one occasion. Once he had fought another prisoner over a crust of bread found under the shirt of a man who had died during the night. Another time a bunkmate had snored too loudly in his ear. Hendrik had won both altercations. His first opponent emerged from their skirmish with nothing but bruises. The second had not been as fortunate. He had suffered a fractured wrist, rendering him unfit for work. Three days later, during selection at the camp hospital, an SS doctor sent him to the gas chambers.

When Hendrik reached Gyuri’s bunk, he snarled in German, “Shut up already, you bastard! Stop wailing!” and he grabbed Gyuri by the armpits and yanked him off his bunk, throwing him to the floor.

Incredibly, Gyuri kept on crying, apparently oblivious to his surroundings. He lay on his back, his knees half-bent, his arms still twitching. A thin trickle of blood dripped from a cut on his temple, where his head had hit the floor.

Hendrik loomed over him, an expression of utter incredulity on his face. He couldn’t fathom how Gyuri could display no reaction to his command to be quiet, let alone being hurled to the floor. Three heartbeats later, the incredulity gave way to blazing fury. The blood rose in Hendrik’s face, and a feral growl rumbled deep in his throat.

“You won’t shut up,” he roared, “I’ll make you shut up.” And he drew back his right leg, intending to kick the crying man.

Jumping to my feet, I got to Hendrik as his foot was already flying toward Gyuri’s unprotected head. He did not see me coming. I planted both hands on his chest and shoved. It wasn’t a particularly hard push. I wasn’t trying to topple him, just keep him from burying his clog in Gyuri’s face. Still, with one foot in the air, Hendrik nearly lost his balance. He staggered back, his feet doing a stuttering shuffle, and he would have fallen had he not managed to brace himself on a nearby bunk.

“That’s enough,” I said.

Hendrik straightened and gave me a stare full of astonishment and rage. He stood with his feet wide apart and his arms slightly bent at either side of him, a stance that hinted at barely restrained violence. His fingers kept opening and closing. I was now between him and Gyuri, who was still on the floor, still weeping.

“Who the hell are you?” Hendrik said. He had a gravelly voice that added to his threatening demeanor. It didn’t surprise me that he didn’t know my name. There were hundreds of prisoners in our block, and, unlike Hendrik, I did not stand out among them.

“My name is Adam,” I answered.

“Why did you push me?”

“To stop you from kicking this man.” I pointed at Gyuri without taking my eyes off Hendrik. I might have added an apology or a mollifying explanation, but Hendrik was a thug, and neither of those things would have appeased him.

“You know him?”

I shook my head.

“Then why do you care what happens to him?”

Back in normal life, the answer would have been automatic. Now I had to think about it.

“I just don’t think we should be killing each other,” I said.

“That would be helping the Germans.”

Hendrik scoffed. “Look at him. You think he’s going to make it? He won’t last a week.”

“That may be. But if he dies, it won’t be tonight, and it won’t be by your hands.”

Behind me, Gyuri let out another howl of agony. Hendrik’s jaw tightened.

“I don’t want to kill him—just to get him to stop making that racket.”

Which might have been true. But Hendrik hadn’t meant to kill the man whose wrist he’d fractured, either.

“Have a heart, Hendrik. The man just lost his wife and six children.”

Hendrik was unmoved. “We’ve all lost family. Every one of us here. We need some peace. We need our sleep. How are we going to make it through tomorrow if he keeps us up all night?”

It was a fair question, and I had no good answer. As though to bolster Hendrik’s argument, Gyuri let out a couple of sharp shrieks, which then dwindled to loud, breathy, grating whimpers. Hardly the sort of sounds conducive to sleep.

Not that our block was ever quiet at night. How could it be, with hundreds of prisoners crammed together in such close quarters, sleeping on bunks that would have felt crowded with a third of their occupants? The moans of the hungry, the groans of the sick and injured, the curses of those jostled from sleep by their bunkmates, the cries of those afflicted by nightmares—these were but a few of the nasty notes comprising the symphony of misery that served as the soundtrack of our nights.

Still, Gyuri’s wails had a unique, piercing quality to them. They rattled my nerves and stabbed at my eardrums as other sounds of anguish did not.

Hendrik offered me a smile that had as much warmth in it as a Hungarian winter. “Fine. I won’t kick him. I’ll be gentle, I promise. Now step aside.”

“No,” I said.

The smile disappeared. He sized me up. He was not as tall as I was, but he had more meat on him. He was also vicious, and he liked to fight.

“Step aside,” he repeated, his voice pitched menacingly low. It was probably a tone that had served him well in his previous life and also here in the camp.

I shook my head.

Hendrik pursed his lips, gave a couple of contemplative nods, and cast his eyes around us. We had attracted an audience. From their bunks, or from where they were standing or sitting, dozens of our blockmates had turned their emaciated heads our way. A few had edged closer for a better view. Some gazed with grotesque curiosity; others looked on with no hint of real interest.

Fights were not rare. You packed this many men into such a cramped space in such squalid conditions and there was bound to be friction. Were it not for our overall fatigue and the need to conserve energy for the next day, we would have been at one another’s throats with much greater frequency.

Hendrik was looking aside when he made his move. It was a ploy to catch me off guard, but I was ready for it. When he swung his fist at my head, I ducked it easily. I moved in under his arm and pushed him again, this time harder. He fell, sprawling on his back with a grunt.

“I’m not looking for a fight,” I told him. “Just stay away from this man.”

Hendrik pushed himself up. He was fuming. But there was also a wary look in his eyes. I was turning out to be a more challenging foe than he had expected.

“You’ve made a big mistake,” Hendrik said. “A big mistake.”

I didn’t answer him. There was a good chance he was right. Why was I risking myself for Gyuri? I didn’t know him. I didn’t really care about him. I wanted him to shut up, too. But I couldn’t allow Hendrik to beat him. The state he was in, Gyuri was incapable of defending himself.

Again, Hendrik looked aside, but this time there was no subterfuge. He caught the eye of two other prisoners, a pair that was chummy with him.

“Marco, Jan, come help me teach this idiot a lesson.”

Marco and Jan were smaller than Hendrik, but both had mean faces. They came to stand beside Hendrik, who gave me a cruel smile. None of the spectators moved to intervene. It seemed they were smarter than I was.

“Last chance,” Hendrik said. “Don’t be stupid. It’s three against one.”

“No,” I said, feeling foolish and even angry with myself.

How did I get involved in this mess? Was I really going to sacrifice myself for this whimpering stranger?

“Good,” Hendrik said. “I was hoping you’d say that.”

Just then, right when the three of them were about to pounce, a voice called out, “Wait a minute!” and I saw Vilmos elbow his way through the crowd of onlookers. He gazed at Gyuri, then at me, and finally at Hendrik and his friends.

“Three against two,” he said, and I was gratified to note that his voice barely quavered.

He was not a formidable man by any means—short, narrow-boned, with a distinct intellectual cast to his features. His voice was equally unmenacing—soft and cultured and slightly high-pitched. The sort of voice that would scare off precisely no one.

I doubted Vilmos had ever been involved in a real brawl. From what he’d told me, his life before the war had been a sheltered one. But here he was, standing at my side, risking everything. My respect for him swelled.

Hendrik and his pals hesitated. The odds were still in their favor, but less so than a minute ago. Still, they had committed themselves. They could not back down now. Not without a good reason.

Fortunately, Vilmos proceeded to provide them with one.

He stuck his hand under his striped shirt and came out holding two pieces of bread. Brandishing them, he said, “For you—if you back off and let us quiet this man down ourselves.”

Hendrik, Jan, and Marco all stared at the bread. I was staring at it too. My mouth hung open, drool dripping down my chin. I wiped it off with the back of my hand, my eyes still riveted to the bread.

My stomach grumbled. The perpetual emptiness ached deep inside me. I could taste the bread, sense its rough, dry texture as my teeth gnawed it to bits. I felt a wild, primitive urge to yank the bread from Vilmos’s hand, even if it meant striking him down.

But I didn’t. I managed to control myself. Maybe I was a man still.

With a grin, Hendrik snatched the bread. “You got a deal,” he said to Vilmos. To me he added, “You’re lucky he showed up when he did. Very lucky.”

Hendrik glanced from the bread to Jan and Marco. He folded the bigger piece and shoved it in his mouth. The other piece he tore in two and handed each a share.

Around the food in his mouth, he said, “Here.”

Jan wolfed down his half. Marco looked about to argue with Hendrik that all three should have gotten an equal share, but in the end, he kept his mouth shut.

When they finished eating, Hendrik asked, “Got any more?”

Vilmos lifted his shirt, exposing a hairless, pasty midriff through which his ribs showed. “That was everything.”

Hendrik ran his tongue over his teeth. A calculating look entered his eyes. “Where did you get the bread?”

“From a dead muselmann,” Vilmos said. “He was still collecting his daily ration. He just wasn’t eating it.”

It was a plausible story. By Hendrik’s nod, I could tell he believed it. Behind us, Gyuri let out a keening wail.

Hendrik glanced at Gyuri and then back at us. His upper lip curled. “He’s still making too much noise. Take him to the back. All the way. If I hear him, if he disturbs my sleep, the deal’s off. Got it?”

Vilmos nodded. Hendrik, Jan, and Marco walked away, the Dutchman laughing and clapping his friends on the back. The crowd of spectators turned their attention away from us.

“Help me with him,” Vilmos said, and together we lifted

Gyuri to his feet and led him toward the rear of the block. It was like moving a mannequin. One that was sobbing.

The deeper we went, the stronger the stench became.

Our block was a converted stable, made entirely of wood. It was divided into eighteen stalls, originally designed for horses. The two in front were reserved for prisoner functionaries: our Blockälteste, the block senior; the three Stubendiensts, who were in charge of order and cleanliness in the block; and the Blockschreiber, the block clerk, who maintained a record of the living and the dead. The fourteen middle stalls contained our bunks. And in the rearmost two stood buckets for human waste, for at night, we were confined to our block and could not go to the latrine.

Each morning, the buckets were emptied, but a noxious cloud always clung to those two stalls and permeated the nearby bunks. During the night, as more prisoners relieved themselves, the stench of urine and feces would grow overpowering. Consequently, no one wanted to sleep near the back of the block. Those who did were either new, weak, or very near death.

This did not mean the rearmost bunks were uncrowded. With over four hundred prisoners in our block, each sliver of sleeping space was used up. Still, Vilmos and I managed to find space for ourselves and Gyuri. Many of the inhabitants of this section of our block were weak to the point of lethargy. They did not complain as we helped Gyuri climb onto a top bunk where only three other prisoners were lying. With eyes that looked massive and hopeless and oddly childlike, they gazed at us in silence as we invaded their cramped, dismal domain. Their thoughts were unreadable. Maybe they lacked the strength to think at all.

Putting my lips close to Vilmos’s ear, I said, “You didn’t really get the bread from a muselmann, did you?”

Vilmos shook his head.

“From where, then?”

He shot me a warning look and whispered, “Not now, Adam. Not here. Someone might overhear us. I’ll tell you tomorrow.”

Then he began to caress Gyuri’s shaved head. He moved his hand gently, as though he were caressing the downy hair of an infant who had awoken from a nightmare. It was appropriate, in a way, though none of us were children. For we were in the midst of a nightmare. One from which we could not awaken.

Gyuri did not seem to notice the touch nor Vilmos’s gentle voice. Vilmos lied to him, told him everything was all right now. Gradually, Gyuri’s weeping subsided and his body relaxed. No longer did his limbs jump about.

He was still in a trance, though. In a tear-choked voice, he began intoning very fast. The words were barely intelligible, flowing into each other with no separation between them. It took me a moment to realize that he was reciting a list of seven names, the names of his wife and six children, over and over again.

--- End of Chapter 1 ---

How Do I Get My Book?

How Do I Get My Book?

Print books are delivered by mail to the address you specified during checkout.

Usually, it takes 6-12 business days to print and ship your book, but our printing service often does it faster.

There may be delays due to holidays or other events beyond our control.

Editorial Reviews

Editorial Reviews

"A genuinely chilling thriller." - CriminOlly

"If you only read one P.I. series, make it the addictive, evocative Adam Lapid Mysteries." - Ellen Byron, bestselling mystery author of the Cajon Country Mysteries

"Jonathan Dunsky's Adam Lapid detective series is full of twists and turns, dark secrets, and thrilling suspense--all set against the backdrop of the end of WWII." - Jewish Book Council

"Recommended for purchase..." - Association of Jewish Libraries News and Reviews

"Jonathan Dunsky knows how to create an intriguing mystery that keeps the pages turning." - Murray Leighton-Bailey, author of the Ash Carter thrillers.

"What a great mystery novel." - Bite of the Bookworm

"I 'binge-read' the entire series." - Cardinal Bluff Reviews

EU Compliance

EU Compliance

Information for customers in the European Union:

Manufacturer details:

Copytech (UK) Ltd, Trading as Printondemand-worldwide.com

9 Culley Court

Orton Southgate

Peterborough

Cambridgeshire, PE2 6WA

United Kingdom

01733 237867

EU GPSR Authorised Representative:

Easy Access System Europe Oü, 16879218

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621, Tallinn, Estonia

gpsr.requests@easproject.com

+358 40 500 3575

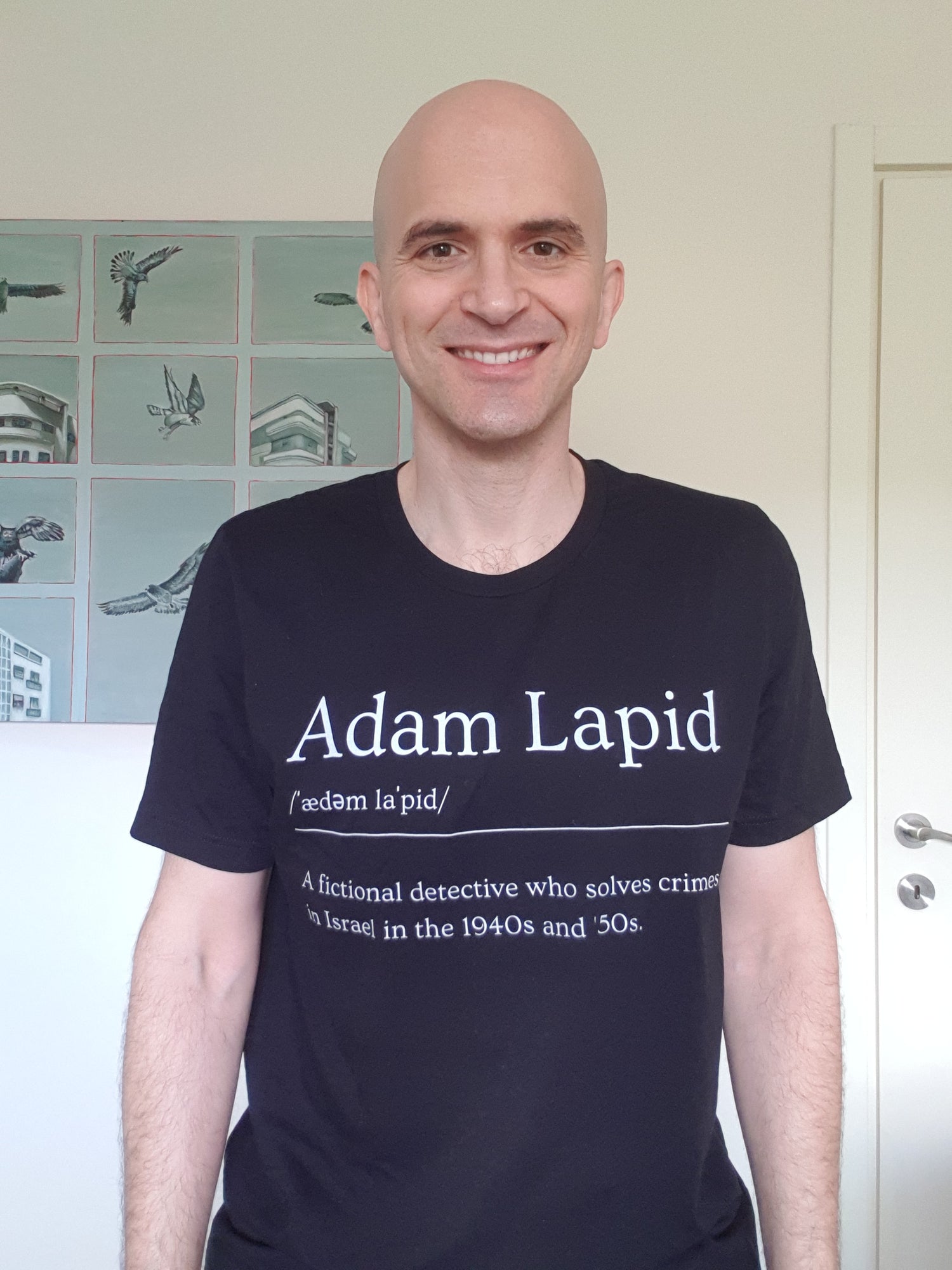

Hi, I'm Jonathan Dunsky

I love history and solving puzzles, so I decided to combine my two passions by writing historical mysteries.

My main body of work is the Adam Lapid series. The Adam Lapid novels are historical mysteries that take place in Israel in the 1940s and '50s.

The one exception is The Auschwitz Detective, a book that takes place in Auschwitz in 1944.

I hope you'll join Adam Lapid as he hunts for crafty killers on the dusty streets of Israel and war-torn Europe.

You can get books 1-8 in the series for 20% off here: 8 Books Bundle.

Uml really was impressed with these boo!Fast read.

Reasonable description of misery of life in Auschwitz . Surprising topic beyond the history and surprising ending. Well written

The Auschwitz Detective (Adam Lapid Mysteries #6) - Hardcover

I haven’t found a book in quite awhile that I just couldn’t put down!

It was a masterful blend of historic and fictional storytelling which kept me thoroughly invested page after page.

I just started Ten Years Gone and am already totally engrossed. I am looking forward to reading the whole series!

Interesting History!!