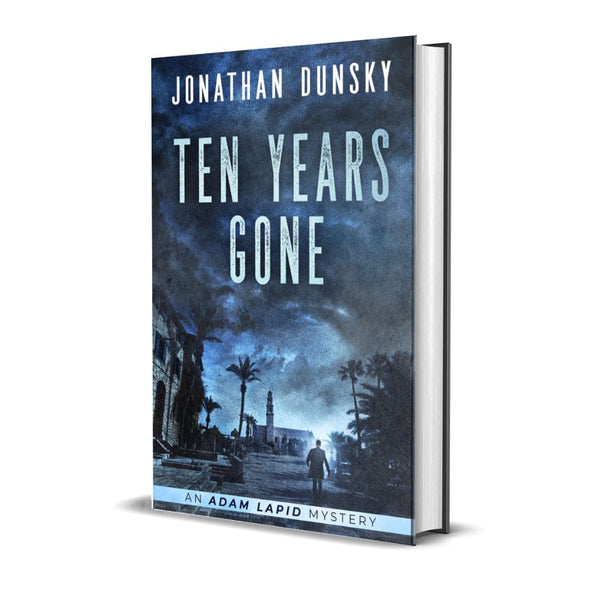

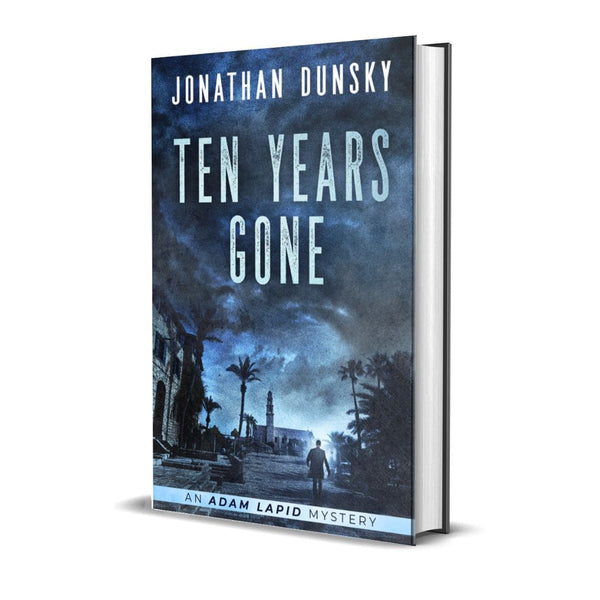

Jonathan Dunsky

Ten Years Gone (Adam Lapid Mysteries #1) - Hardcover

Ten Years Gone (Adam Lapid Mysteries #1) - Hardcover

Couldn't load pickup availability

Book Description:

On the dusty streets of post-war Tel Aviv, a crafty killer roams free…

Israel, 1949 - Private detective Adam Lapid knows how it feels to lose everything. His whole family died in Auschwitz. He barely survived. Now he spends his nights haunted by nightmares and his days solving cases the police won’t handle.

Hired to find a missing boy, Adam thinks the case is hopeless. But he can’t turn down a mother searching for her only child.

What Adam doesn’t realize is that this case will soon put him in mortal danger. For at the root of the mystery lies a double murder that has stayed unsolved for ten long years.

Adam must untangle a web of lies and betrayal to get to the truth. And he’d better watch his back because some of the suspects are willing to kill to keep their dark secrets buried.

Hardcover. Ten Years Gone is book 1 in the Adam Lapid series.

| Hardcover | 344 pages |

| Dimensions | 6x9 inches (15.24 x 22.86 cm) |

| ISBN |

978-965-7795-07-1 |

| Publication date | April 8, 2021 |

| Publisher | Lion Cub Publishing |

Chapter 1 Look Inside

Chapter 1 Look Inside

Chapter 1:

The nightmare tore me out of sleep before dawn.

I opened my eyes, but all I could see were fragments of the dream. Barbed-wire fences and watchtowers. Thick smoke shooting out of tall chimneys, blackening the Polish sky. Uniformed men with evil faces and cruel laughs. Guard dogs straining at their leashes, foaming at the mouth. A huddled mass of frightened, disoriented humanity on the train platform.

With me among them.

What brought me out of the nightmare and into the present was the heat.

July in Tel Aviv was murder, with blazing temperatures and stifling humidity. Nighttime brought only minor relief. It was a favorite topic to grumble about among Tel Avivians.

As hot as it was outside, my room was even hotter. And stuffier. Which was to be expected, I supposed, since I slept with all my windows closed.

I was probably the only person in Tel Aviv to do so.

Or maybe I wasn't. After all, I wasn't the only person with nightmares. Maybe other people were also worried their screams would wake up the neighbors.

Faint echoes of my scream still reverberated in the dark room. My jaw hurt, a sure indication I'd been clenching my teeth during my sleep. I blinked twice, consciously slowing my breathing, until all I could hear was the deep silence of the enclosed room, and all I could see was the darkness around me.

Groaning, I rolled to a sitting position, lowering my feet to the cool floor tiles. Working my jaw from side to side, I stood, stepped over to the window, and pulled it open.

Night air flowed inside, chilling the sweat on my skin. I looked three stories down to Hamaccabi Street below. No people were about. No cars were moving. Somewhere a night bird hooted. Across the street, a baby howled for its mother. The number tattooed on my left forearm itched, and I absently scratched it. I tapped a cigarette out of the half-empty pack on my nightstand, struck a match against the sill, and lit up.

By the time I crushed out the stub of my cigarette, dawn was beginning to paint the sky gray. The nightmare was gone, but it had left its mark. The memories were there, just below consciousness, trying to dig through like burrowing beasts and infest my mind. I had to work hard to keep them away, where they couldn't hurt me.

And I was tired. Dead tired.

Too many fractured nights. Too many nightmares.

I glanced at my bed, at the sheet I had dampened with the sweat of my night terror, at the thin blanket I had twisted around me. I needed sleep badly, but I feared the nightmare would return. There was only one way to keep it at bay, but it wasn't possible tonight.

And I needed my sleep.

With a sigh, I closed the window, got into bed, and pulled the thin blanket over me.

I shut my eyes and waited for the nightmare to reappear.

* * *

"Adam Lapid?"

I looked up from my chessboard at the woman who had said my name.

She was a small woman. Five foot two and thinner than she had any business being. Lackluster blond hair pulled back from a high forehead. A faded yellow dress that had been made with a fuller woman in mind. She held her bag in front of her pelvis, worrying the handle with both hands. I recalled that my mother used to hold her bag like that sometimes.

It was half past four and I was seated at my regular table in Greta's Café. Greta's was a homey café located near the center of Allenby Street, on the block between Brenner and Balfour Streets. Bar and kitchen on the left. A dozen small round tables scattered about the rest of the square space. Above, a lazy ceiling fan rattled with each slow revolution, but did little to dispel the heat. Some of Greta's other customers groused about the rattling, but I hardly noticed it anymore. I frequented Greta's nearly every day. It was more than a place to eat and drink. It was a second home to me.

"Yes," I said and gestured to the chair on the other side of my table. The thin woman lowered herself onto it, setting her bag in her lap. "And you are?"

"My name is Henrietta Ackerland," she said in the tentative Hebrew common to those speaking a new language. She had a pronounced German accent, and for a moment I was about to suggest we conduct our conversation in that misbegotten language. The impulse died fast. Her accent was grating enough as it was.

"Want some coffee?" I asked. "Greta makes the best coffee in Tel Aviv."

Henrietta began shaking her head, but changed her mind when I told her I was buying. Greta had been watching us from her post behind the bar. I raised two fingers in her direction.

While we waited for the coffee, I examined Henrietta Ackerland more closely. She had been beautiful once, but time and circumstances had changed that. Dark bags bulged beneath her washed-out blue eyes. Her lips were thin and colorless. Deep lines ran across her forehead and shallow ones webbed at the corners of her eyes. The lines of someone who did more frowning than smiling.

She was frowning now, two parallel lines etched between her eyebrows. Desperation was weighing heavily on her, crushing her soul. She fixed her tired gaze on me.

"I understand you're a private investigator," she said.

Among other things, I thought. "That's right."

"And you used to be a policeman. A police detective."

"You're well informed."

She said nothing, but the question was clear in her eyes. Why aren't you a policeman any longer?

I hated this part. I did not relish sharing my history. Or explaining my present. But clients needed to be reassured that you could do the job.

"I was a detective with the Hungarian police before the war in Europe. After the war, I came here."

And in between? Well, I couldn't see how that was any of Henrietta Ackerland's business. Nor was it relevant to my abilities as an investigator. Neither was my decision not to become a policeman in Israel.

Thankfully, Greta chose that moment to come over with the coffee, sparing me more of my potential client's questions regarding my past or present. Leaving, she gave me a look that said, Be careful with this one, she's fragile. Greta had a good eye for people. And a good heart for them, too.

Henrietta took a careful sip from her cup, closed her eyes, and nodded appreciatively.

"See?" I said. "I told you it was good."

She gave me a smile that died within one breath of being born. Those smile lines would not be getting deeper any time soon.

I drank from my own cup. "Where did you get my name?"

"From a policeman. Reuben Tzanani. He told me I should see you."

Good old Reuben.

"And you want to hire me?" I said.

"Yes. My son. I want you to find my son."

"He's missing? How long?"

"Ten years."

I raised both eyebrows. "How's that?"

"The last time I saw my son, Willie, was on February 27,

1939. Ten years ago."

Ten years and four months, actually. It was now July 6, 1949.

"And the police couldn't help you?"

"The first officer I spoke with told me it was pointless, that too much time has passed. The second one told me that since the last time I saw Willie was outside the borders of Israel, he couldn't help me. I could see in his eyes that he thought I was a bad mother." There was a sharp edge to her tone, as if this were the greatest insult she had ever suffered. "The third policeman I saw was Reuben Tzanani. He told me you might be able to help."

She was running ahead of me. It was a common phenomenon with clients. They spoke as if you already knew what troubled them, that the formality of hiring you was all that was needed for you to get started on their case.

"Why don't you tell me the whole story from the beginning?"

Instead of speaking, she unclasped her handbag and brought out a small brown book. From its middle, she withdrew a small photograph and handed it to me. The photograph was three inches wide and four inches long. A small piece near the top-left corner had been torn off. The photo was yellowing with age, but the image it showed was clear enough.

A sunny day. A lake in the background. Trees looming on the far bank. Patches of white where sailboats cut across the placid lake surface. A much younger, better-fed Henrietta Ackerland at the front. I could tell it had been a cold day, because she was coated and gloved. A small hat perched on her head. She was cradling a baby. Her son, Willie?

Henrietta was staring directly at the camera, a broad smile across her face. I was right. She had been beautiful once. And happy. The woman who sat across the table from me did not seem capable of such happiness.

"Where was this taken?" I asked, lowering the picture.

"Krumme Lanke. In Berlin. Do you know the city?"

"No."

"It's very beautiful. Or it was, before the war."

"You lived there?"

"Yes. I was born there, went to school there, and got married there. My husband, Jacob, took that picture."

"And this is your son?"

"Yes. Willie is his name. But I said that already, didn't I? He was six weeks old that day."

"Big boy," I said. I would have guessed his age at ten weeks. Neither of my two daughters had looked as big as the baby in the picture at six weeks. "This was how long ago?"

"November 2, 1938," Henrietta said without hesitation.

I turned the picture over. No date on the back.

"You know the date by heart."

She nodded. "It was the last time I was happy, the last time all three of us were happy together. Jacob, Willie and me. Things were turning dark for Jews in Germany, but I had my little bubble of sunshine around me."

Her tone was one of resigned sadness, a sadness that had had time to settle like silt in every vein and artery, never to be dislodged by the passage of blood or time. Her eyes remained dry. I got the sense she had cried so many tears over the past ten years that she had very few left.

It struck me that whatever her story was, I did not want to hear it. I had enough such misery of my own.

Goddamn it, Reuben, why did you have to send this woman my way?

Henrietta said, "One week later, November 9, was Kristallnacht. Jacob was working at the shop. When he did not come back, I thought of going to look for him, but I was too frightened. The noise, the smoke from the fires, the screams. And there was no one to watch over Willie if I went out. The next day, I learned that men had broken into the shop where Jacob worked, dragged him out into the street, and beat him. Then he was arrested. I was sure they would release him soon, but…"

"But they never let Jacob go," I finished her sentence for her when it became apparent she was unable to.

She shook her head. "I tried to find where they took him and kept hoping they'd let him go. After two weeks, I was starting to lose hope. Earlier that year, a cousin of mine decided to leave Germany. She told me I should take my family and leave too, that Germany was no longer safe for Jews. I told her she was exaggerating, that the Germans would soon come to their senses, that the hate couldn't last much longer. By the time I realized she was right, it was too late. Jacob was arrested. I did not want to leave Germany without him. But I could get my son away."

"You gave away your son?" I asked, in a tone of shocked incredulity.

Henrietta flinched as if I had raised a hand to her. "I could think of nothing else to do. I was scared. So scared. I felt that I had to get him out of Germany."

She paused, as if waiting for my approval that she had done the right thing.

"Go on," I said, ashamed of myself. Who was I to judge other people for the decisions they had made in trying to protect their children, considering my failure to protect my own.

"A schoolmate of mine, Esther Grunewald, had decided to immigrate to Palestine. I asked her to take Willie along with her, told her I would follow in a few weeks, three months at most. At first she refused, but I begged and pleaded, offering her nearly all the money I had. Finally, she relented. She and Willie took the train from Berlin to Zagreb on February 27, 1939, and that was the last time I saw my son."

"Why didn't you follow them?"

"I spent the next six weeks making inquiries after Jacob. Then I got a warning that I was to be arrested. Apparently, all my poking about had made someone angry. I used the little money I had left to buy false papers, but couldn't get a passport. I left Berlin, settled in Frankfurt with my new identity, and stayed there throughout the war, hiding in plain sight. With my blond hair and blue eyes, no one suspected me of being Jewish. I looked like the perfect Aryan woman from Nazi posters."

"When did you get here?"

"Two months ago. After the war, I spent some time looking for Jacob, but found no trace of him. I no longer have hope that he's alive. Then I boarded a ship to Israel, but the British stopped the ship and sent us to a prison camp in Cyprus. It was there that I learned Hebrew."

"And once you got here?"

"I started looking for Willie and Esther. I asked the immigration official which newspaper had the biggest circulation in Israel. Davar, he said. I posted an ad there six weeks ago. No one has contacted me. I went to the police, like I told you. Only Reuben Tzanani did anything to try to find Willie. Yesterday he told me he had done all he could and suggested I see you."

"What actions did he take, do you know?"

She nodded. "He told me he checked the civil register, but found no Esther Grunewald or Willie Ackerland listed there. He checked criminal records. Also nothing. Then he searched death certificates from 1939 to today. Nothing." She paused, lowering her eyes for a moment before raising them back to mine. "He told me there was nothing more he could do. I told him I wasn't ready to give up, so he said I might talk to you."

Rubbing the back of my neck, I made a mental note to thank Reuben for leaving me with the unpleasant task of telling Henrietta Ackerland the truth. Which was that her son was dead. It could have happened a number of different ways, but Willie Ackerland was dead, of that I had no doubt. Maybe he and Esther Grunewald had died en route to Palestine. Or maybe Esther Grunewald simply took the money Henrietta Ackerland had given her and dumped the baby somewhere. Maybe she never intended to take him along with her. 1939 was a bad year for kindness. It was a desperate time. In such times even good people do evil things. Maybe Esther Grunewald was such a person.

But whatever had happened, it was clear that no one by the name of Esther Grunewald or Willie Ackerland was living in Israel now or had died here in the past ten years.

I knew I had to tell it to her straight, but that didn't mean I relished the prospect. I delayed by slowly draining my coffee cup. Her eyes didn't leave my face the whole time.

"I wish I could help," I said when I felt I could delay no longer. "But Reuben is right. He checked everything there was to check and found nothing. Finding someone after ten years is almost impossible in the best of circumstances. In this case, there is no hope. With the work Reuben did and the newspaper ad you placed going unanswered, there is only one conclusion to be drawn: Your son is dead."

I didn't tell her I was sorry for her loss. From experience, I knew such a sentiment would provide her with zero comfort. I simply told it to her like it was. The unvarnished, awful, gut-wrenching truth. She would have to deal with it in her own way.

And what she chose was denial. "My son is not dead," she said forcefully, and there was suddenly some color in her cheeks.

"Listen, I—"

She cut me off. "I said he's not dead. If he was dead, I would have known it, I would have felt it. Here." She pointed to her heart. "Do you understand? Do you?" Her face had taken on a resolute cast, her skin stretching taut across her facial bones. It made her look even thinner, as if she might suddenly tear apart from within and whatever was inside of her would come spilling out.

"My son is not dead. He is out there, somewhere, and I need to find him. He needs me to find him. I have no one else to turn to. Will you help me?"

I didn't answer. I couldn't. My throat had constricted and my tongue felt too heavy to move. With my heart racing and the blood pounding in my ears, all I could do was stare at her, at this woman who had harbored an irrational hope for ten years, that at some point she'd be reunited with her son. It was this hope, I was sure, that had kept her going during the long years of the war, even as Germany was reduced to rubble around her. It was this hope that drove her to get up each morning, to put food and water in her mouth, to live.

It took me a long moment to realize I was not breathing. I made myself draw a breath and let it out. Once I was breathing normally again, I knew two things. The first was that she would never give up on finding her son. If I refused to take her case, she would find someone who would. Some in my profession were not the most scrupulous of men. She might stumble upon someone who would not think twice about squeezing her for every penny she had, feeding her tidbits of false hope to keep the money flowing. I would not do that.

The second thing I knew was that I had to take her case. For my sake, not hers. When she told me how she would have felt it had her son died, it was like the butt of a rifle had slammed into the pit of my stomach. I could still feel my insides churning.

I swallowed hard, but the taste of ashes lingered in my mouth.

"All right," I said, my voice nearly cracking. "I'll give it a try."

--- End of Chapter 1 ---

How Do I Get My Book?

How Do I Get My Book?

Print books are delivered by mail to the address you specified during checkout.

Usually, it takes 6-12 business days to print and ship your book, but our printing service often does it faster.

There may be delays due to holidays or other events beyond our control.

Editorial Reviews

Editorial Reviews

"Tel Aviv in 1949 may not look much like Chandler's Los Angeles, but in Ten Years Gone it's every bit as dark in the shadows. Jonathan Dunsky's private eye, Adam Lapid, makes it almost too real." - Lawrence Block, author of the Matt Scudder series.

"If you only read one P.I. series, make it the addictive, evocative Adam Lapid Mysteries." - Ellen Byron, bestselling mystery author of the Cajon Country Mysteries

"Jonathan Dunsky's Adam Lapid detective series is full of twists and turns, dark secrets, and thrilling suspense--all set against the backdrop of the end of WWII." - Jewish Book Council

"I'm as smitten by Adam Lapid as I am with Daniel Silva's Gabriel Alon... I'm compulsively devouring one book after another." - Pamela B. Cohen, author of Hidden Heroes, One Woman's Story of Rescue and Resistance in the Soviet Union

"Jonathan Dunsky knows how to create an intriguing mystery that keeps the pages turning." - Murray Leighton-Bailey, author of the Ash Carter thrillers.

"Ten Years Gone artfully blends history and mystery in a riveting read. " - Faith, Fiction, Friends

"The series combines elements of vintage noir- sharp dialogue, pounding rhythm, high-octane suspense- with bigger themes, treated in a more passionate, dramatic style." - Laurette Long

"I 'binge-read' the entire series." - Cardinal Bluff Reviews

EU Compliance

EU Compliance

Information for customers in the European Union:

Manufacturer details:

Copytech (UK) Ltd, Trading as Printondemand-worldwide.com

9 Culley Court

Orton Southgate

Peterborough

Cambridgeshire, PE2 6WA

United Kingdom

01733 237867

EU GPSR Authorised Representative:

Easy Access System Europe Oü, 16879218

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621, Tallinn, Estonia

gpsr.requests@easproject.com

+358 40 500 3575

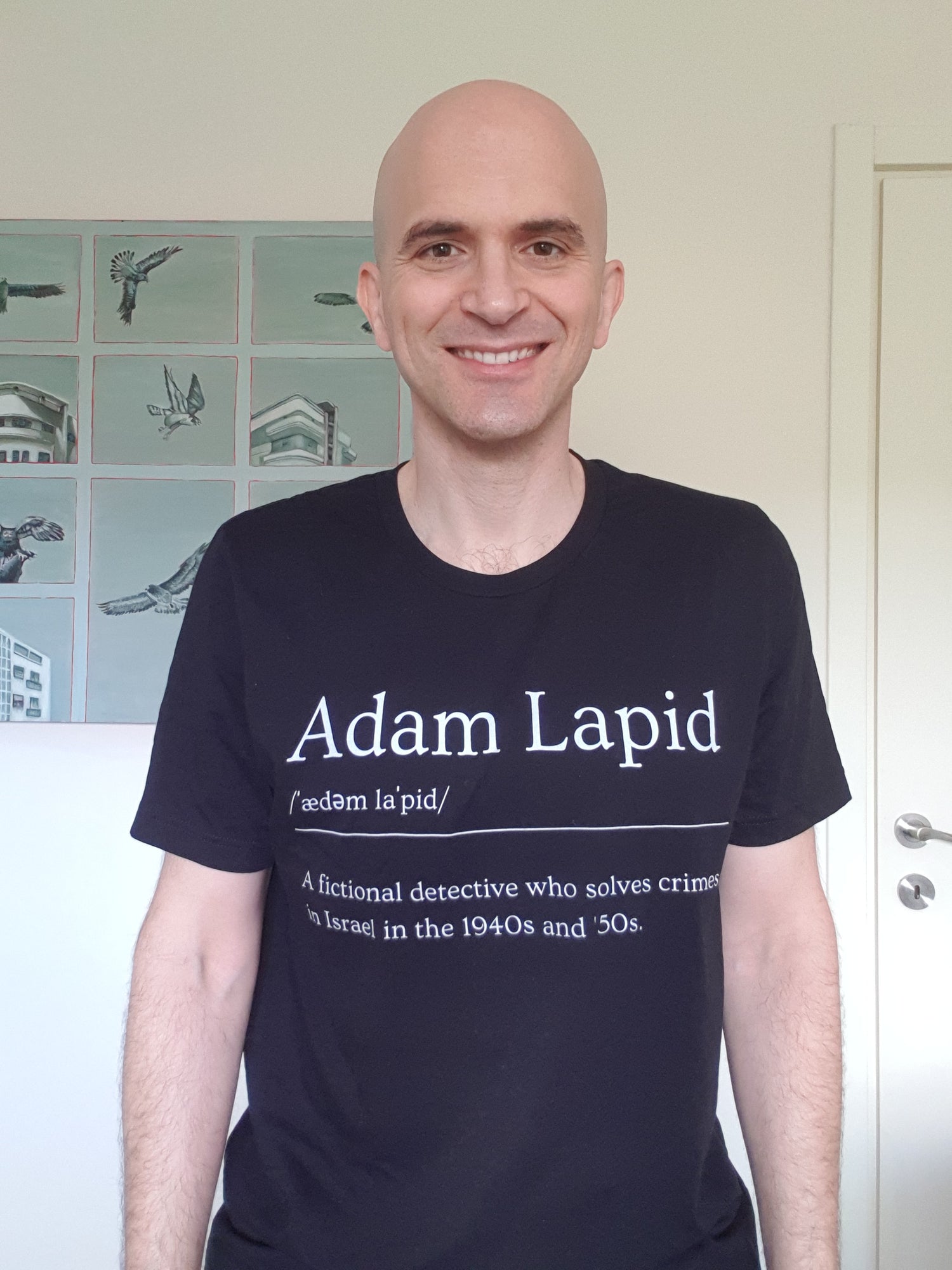

Hi, I'm Jonathan Dunsky

I love history and solving puzzles, so I decided to combine my two passions by writing historical mysteries.

My main body of work is the Adam Lapid series. The Adam Lapid novels are historical mysteries that take place in Israel in the 1940s and '50s.

The one exception is The Auschwitz Detective, a book that takes place in Auschwitz in 1944.

I hope you'll join Adam Lapid as he hunts for crafty killers on the dusty streets of Israel and war-torn Europe.

You can get books 1-8 in the series for 20% off here: 8 Books Bundle.

Excellent read, historical

Great book great story. Couldn't put it down

I have enjoyed all of the books that I have read do far. They are very interesting and they keep you riveted to the stories. It makes me feel like I am there.

do not send any more items.

Great book, easy reading, with lots of good twists in the plot! Looking forward to reading the other books in the Adam Lapid series